Avoid these THREE mistakes in demonstration lessons

Demonstration lessons are part of being a teacher. In a previous post, I’ve put together a guide on how to create an A+ demo lesson. In this post, I’ll go through some common mistakes that teachers make in demo lessons.

Mistake #1: Too much complexity

Teachers are keen to impress during a demo lesson. You’ve got this narrow window to showcase your skills and abilities, so there may be a temptation to include a wide range of content.

Problems can arise when teachers include too much content, in too much detail. In my experience, if a teacher’s included too much content, the following things can happen:

the teacher speeds up — substantially — to try and fit all the content in. This can affect student engagement and understanding

the teacher feels stressed and frustrated when it’s clear the content won’t fit into the lesson

the teacher addresses some of this frustration and stress toward the students. This is never a good look.

Keep your lesson simple. Be clear on what students need to take away from the lesson and don’t vary widely from this focus.

Also, make sure you teaching style is simple and concise. Avoid complexity. If there are definitions, give them to students, don’t make them try and guess them. Put the information on slides or written on the board and avoid extensive lecturing.

Mistake #2: Too much technology

Technology is a vital teaching tool. Teachers are expected to be comfortable with a range of technologies to assist with student engagement and understanding.

In a demonstration lesson, you should show a base level of competence with technology. But don’t go overboard.

If you have many technological elements, each interdependent and requiring things to unfold in a very specific way…you may be creating problems. For a demo lesson, keep the tech simple. Show you can use PowerPoint or Slides; that you can use videos (which have also been downloaded in case the internet goes down); and that you can use Word or Pages or Canva to create materials for students.

It’s great that you can use Kahoot! or NearPod or Limnu. But is a high-pressure demo lesson the best time to deploy all these?

Keep it simple. And have print outs of your slides for your reference in case tech really fails you.

Mistake #3: The wrong type of activities

Choose your activities carefully.

For example, if you read out a whole article together as a class, then ask students to complete related questions, this may not demonstrate a wide range of teaching skills.

Likewise, is a cloze passage activity suitable for a senior class? And should you be asking true or false statements, multiple choice questions or more open-ended responses?

Go back to the purpose of the lesson and pick an activity that matches well to this.

As a general plan, you could think about this kind of structure:

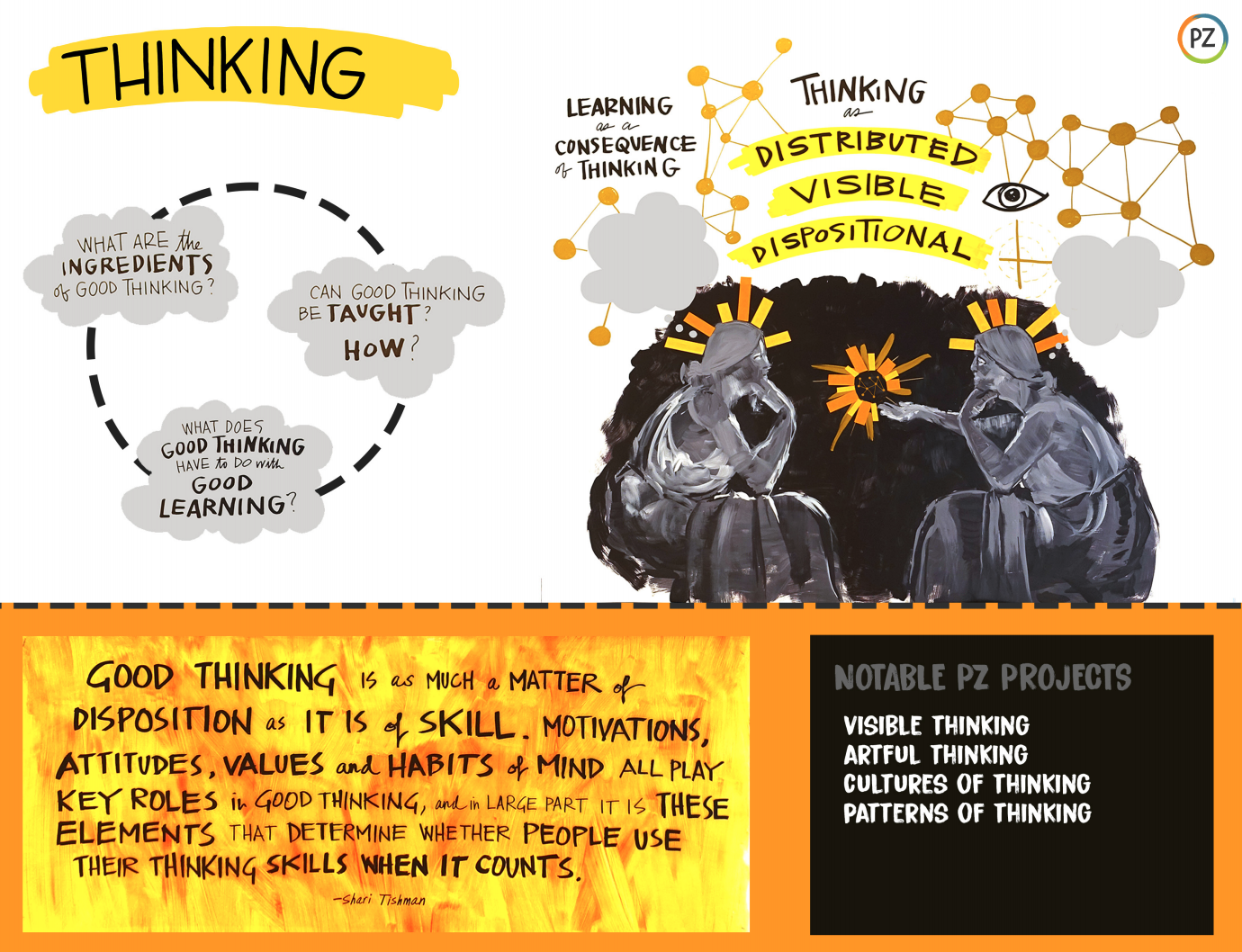

Introduce a stimulus to the class — it could be an image, quote, headline, video or excerpt from an article (only an excerpt — not the whole thing!)

Pose a question based on the stimulus. Ask students to think about this individually and write down their ideas

Get students to pair up with the person next to them and share their responses. Ask them to create a combined response

Come back together as a class. Make sure you, as teacher, connect the responses back to the content you discussed at the start.

Check out the video below for more detail on the mistakes to avoid in your demonstration lessons.