The circular flow of income: problems with the model

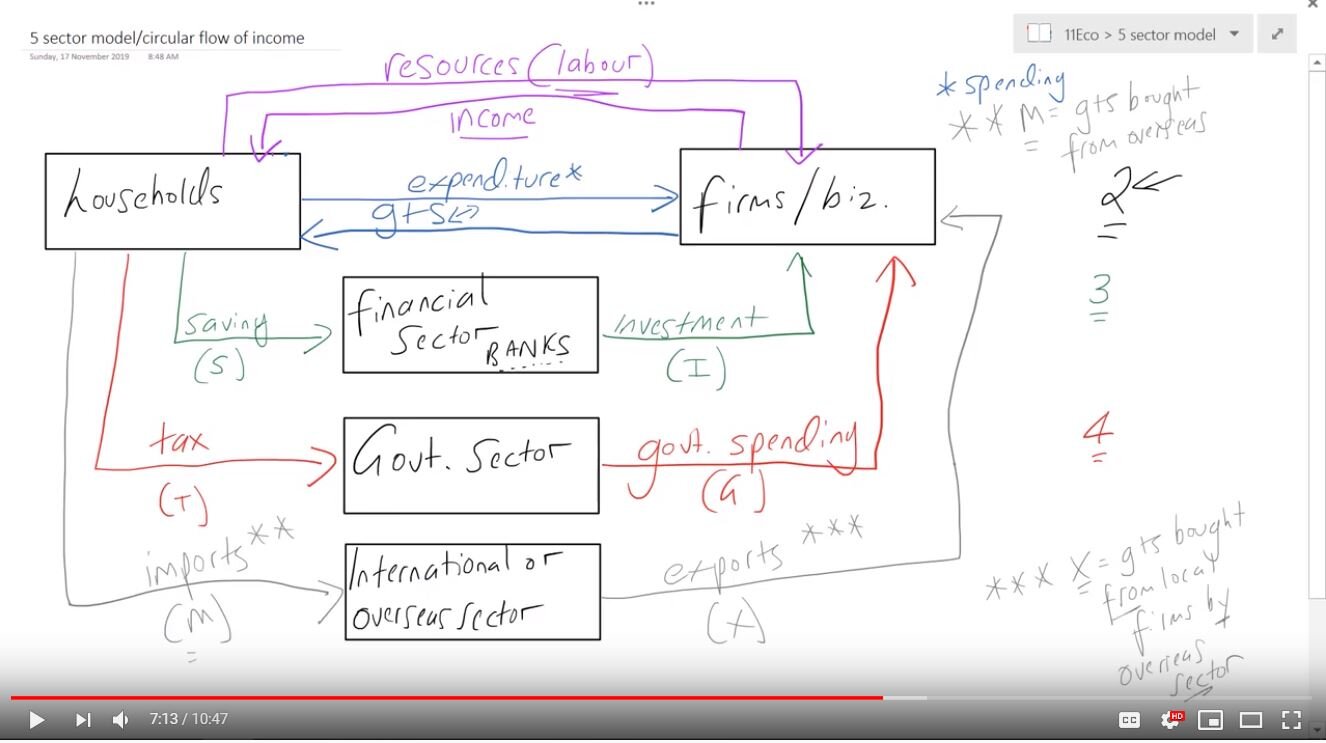

As part of your Economics study, you’ve probably done the Circular Flow of Income Model. This is also known as the Five Sector Model or the Five Sector Circular Flow of Income Model.

Here’s my explainer on the model. I’ve also written about how the Circular Flow of Income Model helps us understand economic growth.

The Five Sector/Circular Flow model is useful. I like it a lot, I use it all the time. But it’s not perfect. Here are some limitations you should be aware of.

A general limitation: The model heavily simplifies the economy

An economy is an extremely complicated thing. Can we really simplify something so complex into five sectors and 10 flows?

Just think about the household sector. Do all individuals within households act in exactly the same way? What about firms, or financial institutions? It’s hard to lump all these groups into one category and assume they will all take identical actions.

In addition, central banks play a huge role in the economy. They affect the supply of funds, which then indirectly affects the level of interest rates (this is Monetary Policy). This is absent from the model.

A specific limitation: The model excludes households borrowing money from banks

Take a look at the financial sector, which includes banks. According to the model, households deposit their savings with the financial sector.

But where is household borrowing?

The model does show the financial sector investing in businesses — lending firms funds so they can expand and grow. However, the model does not show households borrowing money from banks.

This is a huge flow in the economy. For example, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), in December 2021, households took out nearly $33 billion of new home loans — either to buy a property to live in or to rent out. This is a massive injection into the economy but is excluded from the model.

Likewise, household loan repayments — an ongoing leakage — are also absent.

Another specific limitation: The model excludes firms buying imports

The model shows households buying goods and services from overseas (imports). You can see the flow of money going from households to the international sector. Yet, the model does not show firms buying imports.

Just think about all the goods and services Australian businesses purchase from overseas:

a restaurant purchases fancy cheese from Italy

an outdoor recreation store (like Anaconda) purchases stock from overseas to then sell to local customers

a school buys online products — such as access to the Google or Microsoft suite of products — and this involves money leaving Australia.

These purchases represent a huge flow of income. According to the ABS, in the September quarter of 2021, imports of capital goods (which are mainly done by businesses) totalled around $1.4 billion.

Do these limitations matter?

If we’re using this model to understand the basics of the economy, then no. It helps us understand the mechanics of how money moves around an economy and how the sectors interact with each other.

But like all models, it’s got limitations. We need to know its limitations so we don’t ask the Circular Flow of Income to do too much.